Tech giants point to miners in money game

Major tech firms have sent their people to appear before the Senate hearing on multinational tax rorts, but they did not reveal much.

Major tech firms have sent their people to appear before the Senate hearing on multinational tax rorts, but they did not reveal much.

Accountants and other representatives from Google, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook spoke at the Senate inquiry on corporate tax avoidance in Sydney, where most admitted to some sort of tax-dodging, and brushed it off as just a part of business.

Funnelling money through “marketing hubs” in Singapore emerged as a common practice.

Microsoft said it has sent $2 billion of revenue from Australia to Singapore for taxation purposes, and Google admitted to using Singapore-based hubs too, but would not disclose how much it had sent there.

Google’s managing director in Australia, Maile Carnegie, said that for a company like it to pay most of its tax in the US (where its intellectual property and research are held), is just like any Australian mining company that sells the bulk of its product overseas, but pays tax in Australia.

“If you look at someone like a Rio Tinto, they have 35 per cent of their customer base in China, but less than 1 per cent of their tax in China ... so if I look at it, Google has a similar structure.”

If an Australian company books a Google ad in Australia, the payment is routed through Singapore, where the tax rate is much lower.

This is a simple example of the tax-dodging practice that tech companies employed.

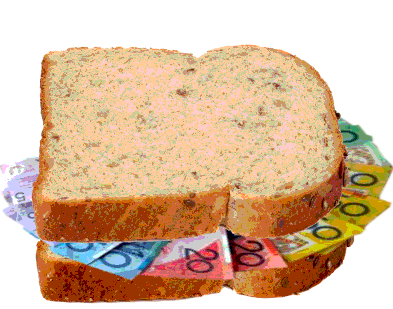

At the other end of the complexity scale is the fantastically named double Irish sandwich with a Dutch twist.

This practice sees companies send profits through one company in Ireland (where both Apple and Google have offices) then through a Dutch company (to take advantage of lower tax rates), before being returned to a second Irish company, and on to a company headquartered in a tax haven like Bermuda or the Cayman Islands.

Australian-based companies (miners in particular) employ the simpler option – selling their products at a discounted price to Singapore’s “marketing hubs”, which then re-sell them at full price.

ATO commissioner Chris Jordan has told News Corp reporters that new legislation could help deal with the use of marketing hubs.

“The hubs are a pure transfer pricing issue. And we have some new transfer pricing laws in there that are yet to be tested. They are a lot better than the old ones,” he said.

“The new law uses what is known as the counterfactual. It allows us to reconstruct the transaction. On the best available evidence this is what we think you would’ve done and this is how much tax you should’ve paid.

“So in the last year and a half of transactions, we are looking at marketing hubs through a different lens. We need to test this in court as soon as we can to get some judicial commentary around our ability to reconstruct transactions. We are pretty happy with the transfer pricing agreements as they exist now, but they are only about two years old.”

But there is very little that can be done in a single country to stop profits being laundered without broader international efforts.

Treasurer Joe Hockey has hinted that a diverted profits or “Google tax”, as is being introduced in the UK, could be an option.

In an article for The Conversation, local tax experts warned against hasty and potentially ineffective changes.

“They don’t even know how they’re going to try to calculate the revenue that they’re going to collect from Google,” Challis Professor of Law at Sydney University, Richard Vann said.

He said Australia was sending contradictory messages by suggesting in its tax discussion paper that the corporate tax rate should be cut, while also claiming that tax avoidance by multinationals was depriving domestic coffers.

QUT taxation Professor Kerrie Sadiq agreed, and said Australia must collaborate internationally and not act “hastily or unilaterally”.

“Personally, I believe we should strive to fix the current system, particularly the transfer pricing regime.”

Antony Ting, Associate Professor at University of Sydney, said the ideal solution was international consensus, like the OECD BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) project.

“I think Australia should continue to support the OECD project, we will get something out of it, but we should also think about plan B,” he said.

But, Ting said, the OECD’s plan would only be effective if the ATO was given more resources to help it implement reforms, and as much information about tax structures as the multinationals it investigates.

“There is a lack of confidence in the corporate tax system and the public is calling for corporate social responsibility in relation to tax not just compliance with tax obligations,” he said.

“Unfortunately, very few corporations view tax as an economic contribution to public finances.”

Print

Print